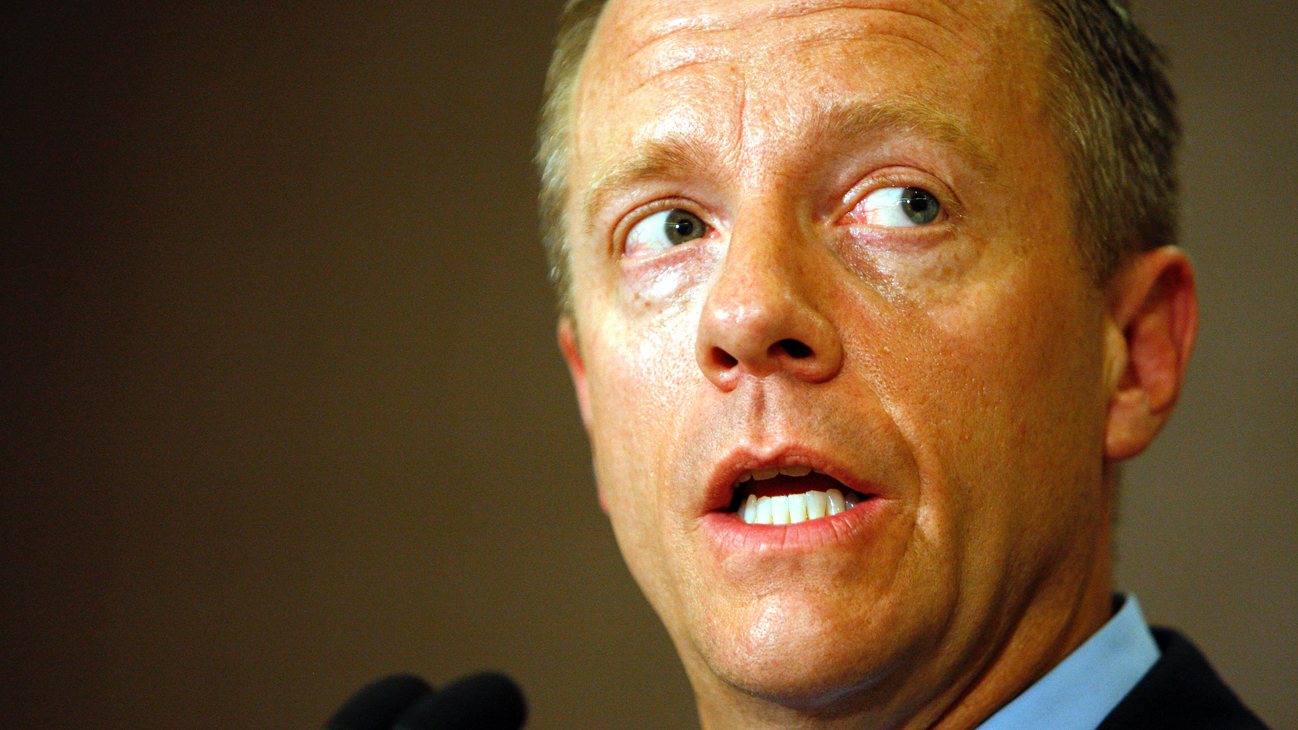

Ontario’s former attorney general is opening up about the life-changing experience he went through in Toronto nearly three years ago, when he was involved in an incident that claimed a cyclist’s life.

Michael Bryant spoke to Amanda Lang about the night that Darcy Allan Sheppard died and the subsequent criminal charges laid against him, which were eventually dropped.

“When I found out he died … that was the worst,” said Bryant, who in his book about the incident, 28 Seconds: A True Story of Addiction, Injustice and Tragedy, also reveals for the first time publicly his own battle with alcoholism.

The incident occurred on Aug. 31, 2009, a night when Bryant and his wife, Susan Abramovitch, were out celebrating their anniversary.

They were sitting in their convertible, in a line of traffic on Bloor Street, when they first saw Sheppard.

Some garbage and pylons had been strewn about the street “as if someone had created an obstacle course for the cars,” Bryant said.

He and his wife could see Sheppard at the corner of Yonge and Bloor streets.

Bryant said Sheppard appeared agitated and intoxicated.

“He was raging and he was throwing garbage on the street and he was screaming at someone through his car window, just screaming at someone,” he said.

“And I assumed that he’d moved the pylons as well.”

Bryant got out of his car and moved some pylons out of the way. Traffic started to move past Sheppard, who subsequently rode ahead and caught up with the stream of vehicles. Bryant said the man was riding his bicycle in “figure eights” on the road.

“It was stunning, I’d never seen anything like it … he was weaving in and out of ongoing traffic and laughing and he seemed to be enjoying that moment,” said Bryant.

Bryant and his wife would soon pass Sheppard’s bicycle, but the cyclist soon came up to his car and “took a swing” at the former provincial cabinet minister.

To this day, Bryant said he doesn’t know why Sheppard confronted him. But the seconds-long altercation that followed would change both men’s lives forever.

Bryant said he tried to get away from Sheppard, at first struggling to get his vehicle started, though it lurched forward at one point and he hit the brakes.

But that made the situation worse.

“Something was triggered and he went to a whole other level of rage,” Bryant said.

Bryant began backing his vehicle away. When he got his vehicle moving forward again, Sheppard came at the car.

“He started running at the car,” said Bryant.

Bryant said Sheppard jumped on the car while he was driving. As the man tried to get into the vehicle, Bryant slowed down, but Sheppard held on.

But he would fall as Bryant drove on. When Sheppard was off the vehicle, Bryant pulled over at a nearby hotel and called police.

That evening, Bryant was arrested and taken into custody.

He later found out from his lawyer that Sheppard had died.

“She said: ‘Michael, he’s dead. He died,'” Bryant said.

Bryant said he put his head in his hands.

Learning what had happened to Sheppard was “the worst part of it for me … being associated with a person’s death,” Bryant said.

Within hours, Bryant faced charges of criminal negligence causing death and dangerous driving causing death.

But those charges were later dropped after the Crown was informed about prior altercations Sheppard had with people in vehicles. Video evidence also helped confirm Bryant’s account of what happened on the street.

Bryant said the initial stories from that night suggested he was involved in a road rage incident “with an unnamed blonde in Yorkville after a night of celebrating.”

“I was sober that night,” said Bryant, who writes in his book that he finally gave up drinking in 2006 and only drank a Nestea on the night of Sheppard’s death. “I offered to take a breathalyzer and they [the police] for whatever reason said no, I guess because they didn’t need to.”

Book an ‘offering’

Nearly three years on, Bryant said the experience has made him more humble and less focused on what other people think of him. It has also left him less certain of what lies down the road in his life.

“I’ve always had a master plan and 10 backup plans and a small team of advisers to figure out and test and adjust and innovate it. And there is not a plan,” he said.

When asked whether he felt a kinship with Sheppard over their common struggles with alcoholism, Bryant said he didn’t want to overstate their connection. But he added he and Sheppard likely were “in the same rooms” in their attempts to get help.

“We might have been in the same rooms of recovery at the same time but … I don’t know we were,” he said. “We were definitely in the same rooms, maybe not at exactly the same time.”

Asked by the CBC’s Lang why he chose to write the book, Bryant said it’s “an offering” to help those who are facing a “challenge” in the criminal justice system and show they are “not alone.”

“It’s meant to share lessons learned from an attorney general who was charged with killing someone and the perspective that comes with that,” he said.

“Many people have had the perspective of being in the criminal justice system and many people have had indescribably worse experiences — a wrongful conviction for example.

“But they didn’t used to run the system, and I got to run it for four years.”

Reading other people’s stories of addiction and recovery, he said, helped him get sober.

“I knew that here was an opportunity for me to do something like that, you know, lessons learned and here’s how I got through a crucible,” Bryant said.

“It’s just, you know, here’s my experience and hope. And you know, for the suffering alcoholic, yeah, it’s brutal, but this way is better. Sober, better…. You’ve got to give up, you’ve got to surrender. You’ve got to cross over to the winning side.”

From CBC.ca; August 20, 2012