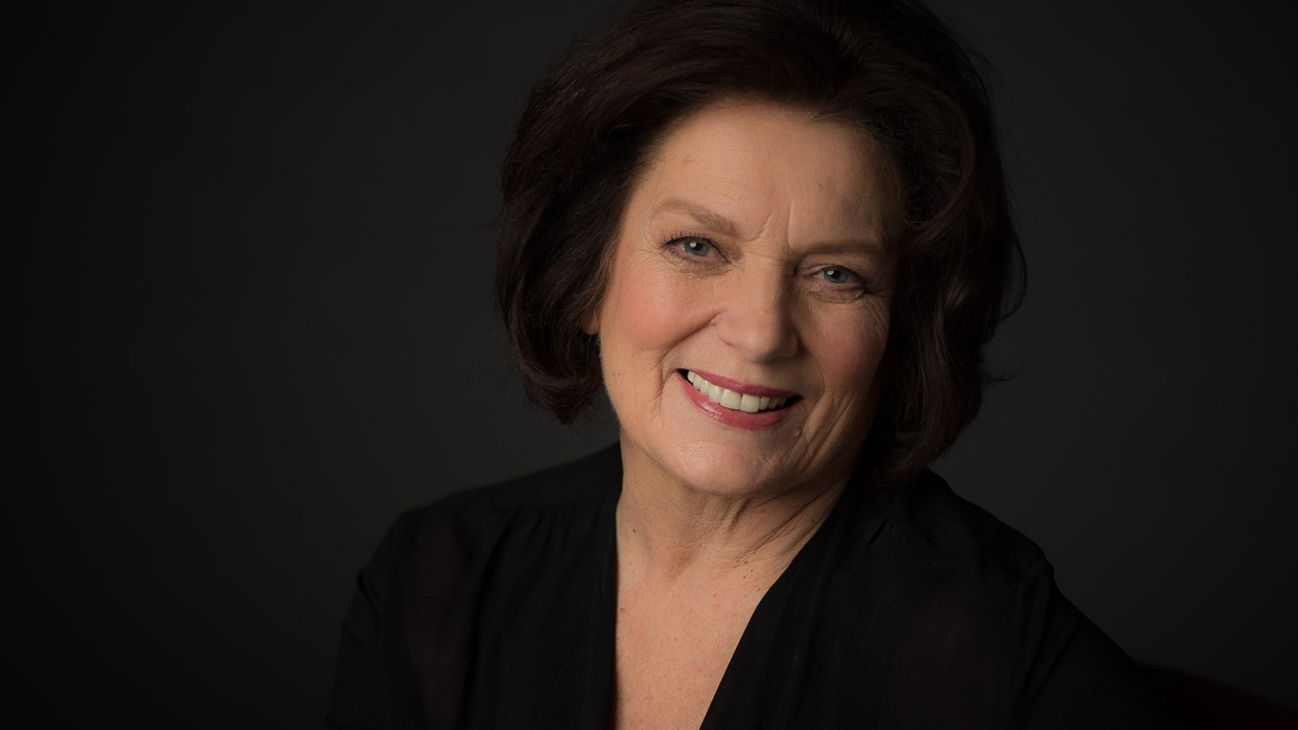

Margaret Trudeau is a Canadian icon, celebrated both for her role in the public eye and as a respected mental-health issues advocate. From becoming a prime minister’s wife at a young age, to the loss of both her son and her former husband, to living with bi-polar disorder, Margaret tirelessly shares her personal stories to remind others of the importance of nurturing the body, mind, and spirit. Last week, Margaret was profiled in The New York Times, shortly after her son, Justin Trudeau, was sworn in as Canada’s newest prime minister:

On Wednesday, Justin Trudeau took the oath of office as the new prime minister of Canada, accompanied by his wife and three small children — and a woman in a dark blue coat that many people in the country may not have seen much of in recent years but who remains an indelible character in Canadian political history: his mother.

Justin’s father, Pierre Elliott Trudeau, is still, 15 years after his death, the only former Canadian prime minister most people from outside the country can probably name. And Margaret Trudeau still reigns as the most famous wife of a Canadian prime minister.

Less than half the prime minister’s age when they married in 1971, Mrs. Trudeau, suddenly went from being a hippie who had been wandering around North Africa to the world’s most glamorous first lady. Then as her marriage to the cerebral Mr. Trudeau began crumbling, she found even greater fame, of a very different sort.

Partying with the Rolling Stones, watching the scene at Studio 54 with Andy Warhol and being tutored in photography by Richard Avedon made Mrs. Trudeau, then the mother of three young children, global tabloid fodder. And with last week’s swearing-in of the oldest of those children, Justin, 43, Mrs. Trudeau became the first person to be both the wife and mother of Canadian heads of government.

The ceremony also brought Mrs. Trudeau back to Ottawa, a city where she found little peace in the past, as well as back to the public spotlight.

“Everywhere I go, particularly when there’s people who know me or recognize me, I get the warmest hugs and happiest sighs full of hope and full of relief,” she said, from Montreal, in a telephone interview on Friday. “It’s been such a rejoicing in our family and I have felt it from all the emails, letters and phone messages — everything.”

After losing interest in Mrs. Trudeau, who is now 67, much of the world then missed the back story to her New York escapades as well as the sometimes harrowing tale of the rest of her life, which includes the tragedy of a lost son. Mrs. Trudeau was judged and condemned by many Canadians for — as it was generally, if not entirely accurately, seen at the time — abandoning her children.

Over the last three decades, it has become clear that Mrs. Trudeau’s actions, while often seen as selfish and sometimes outrageous, were the product of a long hidden battle with bipolar disorder, one that would put her in a straitjacket and a padded cell. Today Mrs. Trudeau is not just Canada’s first grandmother, she is also one of the country’s leading advocates for mental health patients.

In her memoir, “Changing My Mind,” published in 2010, Mrs. Trudeau recalls not being particularly impressed by her future husband when they first met on the island of Moorea in Tahiti. She was on vacation with her parents and sisters; he was there to mull over seeking the leadership of the Liberal Party.

Mr. Trudeau was reading “History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire,” which struck her as an odd choice for a holiday. “My first thought was that he was old, with old skin and old toes,” Mrs. Trudeau wrote.

After graduating from Simon Fraser University in her native British Columbia, Mrs. Trudeau made her way to Morocco and “wandered from one hippie colony to another, experimenting and growing up — or so I imagined.” After she returned to Canada, Mr. Trudeau, a longtime bachelor, looked her up for a date while he was out in British Columbia.

Based on an offhand comment from him that evening, she moved to Ottawa and took a job as a government sociologist. Neither the capital city nor the work suited her. But Mr. Trudeau did. He may have had old toes, but he was as athletic as he was intellectual. Photos of Mr. Trudeau skiing or canoeing, often in a buckskin jacket, regularly appeared in Canadian newspapers. They married in March 1971. She was 22, he was 51.

Within the next few years, Mrs. Trudeau gave birth to three boys. The two oldest, Justin and Alexandre, who is known as Sasha, were both born on Christmas Days. The youngest, Michel, came to be called Miche (pronounced “Meesh”), a name given to him by Fidel Castro during a state visit to Cuba.

Whatever Mr. Trudeau’s charms, living with his mother well into middle age proved not to be ideal preparation for life as a husband, a situation made worse by his heavy work schedule. And while he was wealthy thanks to his father’s success in the gas station business, Mrs. Trudeau soon discovered that her husband was an exceptional tightwad.

Worst of all, particularly for someone already struggling with undiagnosed bipolar disease, was living under the constant guard of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police. Mrs. Trudeau wrote that 24 Sussex Drive, the stone mansion which is the prime minister’s official residence, “was the jewel in the crown of Canada’s penitentiary system in which I was the sole prisoner.” (Because that house will undergo renovations for at least two years, Justin Trudeau and his family are living in another government house.)

Last week, Mrs. Trudeau said that she didn’t expect her daughter-in-law, Sophie Grégoire, 40, to endure similar struggles given her age and her background as a television host.

“She’s a very curious and inquisitive person,” said Mrs. Trudeau of Ms. Grégoire, “so she’s always reached out for help. The opposite of me. I was always young, and I had none of these lessons under my belt and I didn’t know how to ask for help. Sophie is a magnificent woman.”

As she has noted, Mrs. Trudeau did not always deal with the pressure wisely. Before giving a speech, which became “a song of love” during a state dinner in Venezuela, Mrs. Trudeau ate peyote. “Even in my addled state, I could sense the acute embarrassment I had caused,” she later recalled. After a visit to the United States, Mrs. Trudeau became infatuated with Senator Edward M. Kennedy, who she found to be more sympathetic than her husband.

Prompted by one of her manic periods, Mrs. Trudeau decided to live part of the time in New York and develop a career in photography. Following what became an infamous trip to Toronto to party with the Rolling Stones, she left Canada to study with Richard Avedon.

While Mrs. Trudeau became a recognized photographer, the New York foray marked the start of the gradual end of her marriage and the beginning of a series of out-of-control episodes, several of which landed her in hospitals. Most of the related episodes of bad behavior were dutifully reported in Canada and by Britain’s tabloid press.

Amid the downs, there were good periods. Among them was her marriage to Fried Kemper. The two children from that marriage, Alicia and Kyle Kemper, have enjoyed the anonymity denied their mother and half-siblings.

But when Michel was killed by an avalanche while skiing in 1998 that marriage, and Mrs. Trudeau’s life, began to truly collapse.

During an interview in 2013, Justin Trudeau said that following the death of Michel, his father, who died two years later, “never bounced back physically, and that was that. And my mother, who has struggled with bipolarity all her life; it took her five years to be able to get over, be past and get to a place of balance and joy.”

Mrs. Trudeau attributes the stability that has finally came to her life largely to the patient work of Dr. Colin Cameron, a psychiatrist at the Royal Ottawa Mental Health Center, a mental health center.

“I had to go into such deep, deep treatments to get my brain health back, to get my mental health back, after I was thrown to the ground,” she said. “But that was then. Now I think we can shorten the time between diagnoses and recovery.”

The hospital also led Mrs. Trudeau into what is an improbable career for someone who spent most of her life trying to escape public scrutiny. After being persuaded to speak at one of its fund-raising events, Mrs. Trudeau said that she found that she had a talent for it and now regularly holds talks about mental health throughout Canada. In the past they have included mother-son talks with Justin.

And in addition to her 2010 memoir, she published a self-help book for older women this year.

Justin Trudeau’s rise to power has prompted something of a reassessment of Mrs. Trudeau. Neil Macdonald, now a senior correspondent for the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, was once a newspaper reporter who covered Mrs. Trudeau and questions how she was treated by the press.

“She was guileless, and we were predatory,” he wrote in a recent essay. “Our stories were full of snide references to the ‘flower girl’ our Jesuitical prime minister had brought home.”

In 2007, Mrs. Trudeau moved to Montreal to be closer to Sasha and Justin, their wives and her grandchildren. As a bonus, she has been able to lead a more anonymous life in the much larger city.

Her son’s succession of her husband as prime minister, however, will now draw Mrs. Trudeau back to Ottawa more frequently, even if she is a bit ambivalent about her return to prominence.

“Who am I,” she said on Friday, “Canada’s Rodney Dangerfield? I get no respect. I don’t care about the respect of the press or the public or anybody. Whose respect every day I’m trying to garner is the respect of my children and my grandchildren and my friends, the people I work with. I find myself now in a position in life where I’m so comfortably in place — but unfortunately I’m getting old.”

Ian Austen/New York Times/November, 2015